After This Election All I Can Hear In My Head Is Raed Fares

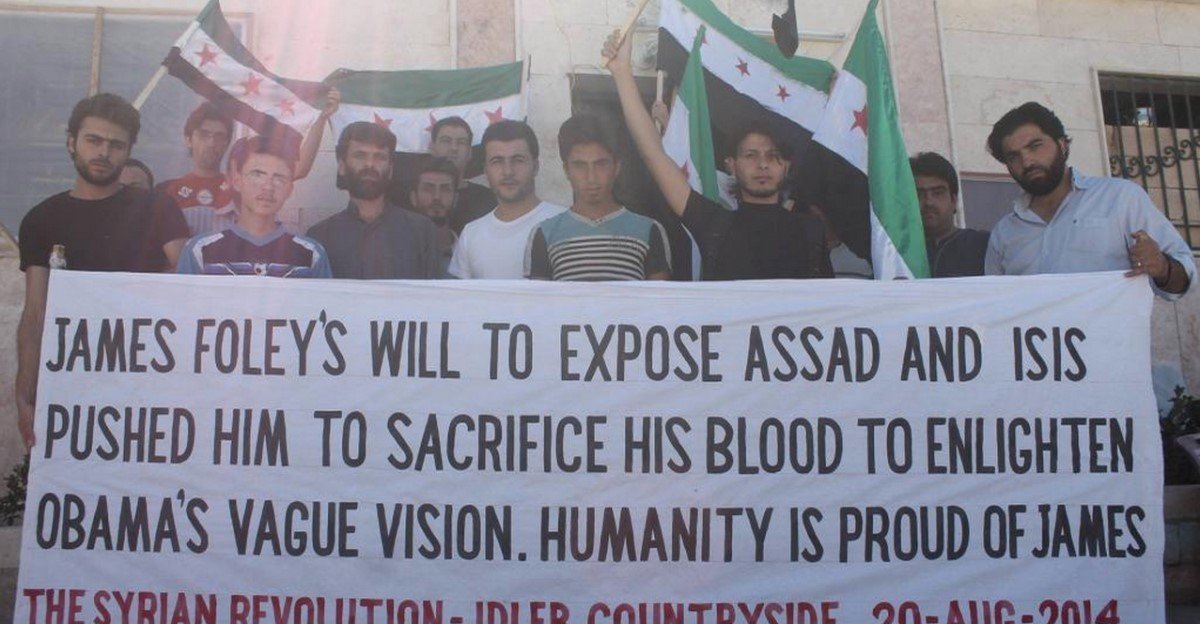

A message from the Syrian activists of the small town of Kafranbel, Idlib Province, to then-candidate Donald Trump after he praised Putin

I'm writing this on the morning after the election. Like many of you, I'm in a daze. This morning, many Americans are afraid—and for good reason. In 2016, Trump pledged to take drastic, often unconstitutional steps; some were blocked by his own staff. Now he’s pledged even more extreme actions and has spent four years ensuring that no one stands in his way. With Republican control of the lower courts, the Supreme Court, the House, the Senate, and Trump as President, he may attempt them all—and very little stands in his way.

But if you’re reading this, you already know the stakes, and I don’t need to paint the nightmare scenarios running through our minds. I, too, am afraid.

But that's not what I want to write about today. Since waking up this morning, one voice keeps echoing through my head: the voice of a man who was my friend, the voice of a man who was murdered for what he believed in. And he knew he would be murdered, and I knew he would be murdered, and he still held on to hope.

So today, I want to tell you about my friend Raed Fares.

The End of Everything

In 2011, the Syrian people had had enough. They were hungry, thirsty, tired of living in poverty, and exhausted by the constant fear of retribution for speaking out. Inspired by the "Arab Spring" protests that started in Egypt and Tunisia, Syrian society rose up, and Raed Fares became one of the movement’s loudest, bravest voices.

Raed lived in a small town called Kafranbel, a rural community in northwestern Syria’s Idlib province. There, people made their living farming figs and olives, praying for rain that often never came. The Syrian government had long neglected this place while relying heavily on the food it produced. Raed himself was not poor, not compared to many others, but he saw how the regime beat, arrested, and killed protesters who just wanted a better life, and he began to protest himself.

It turned out that Raed, though soft-spoken, had one of the loudest voices on earth.

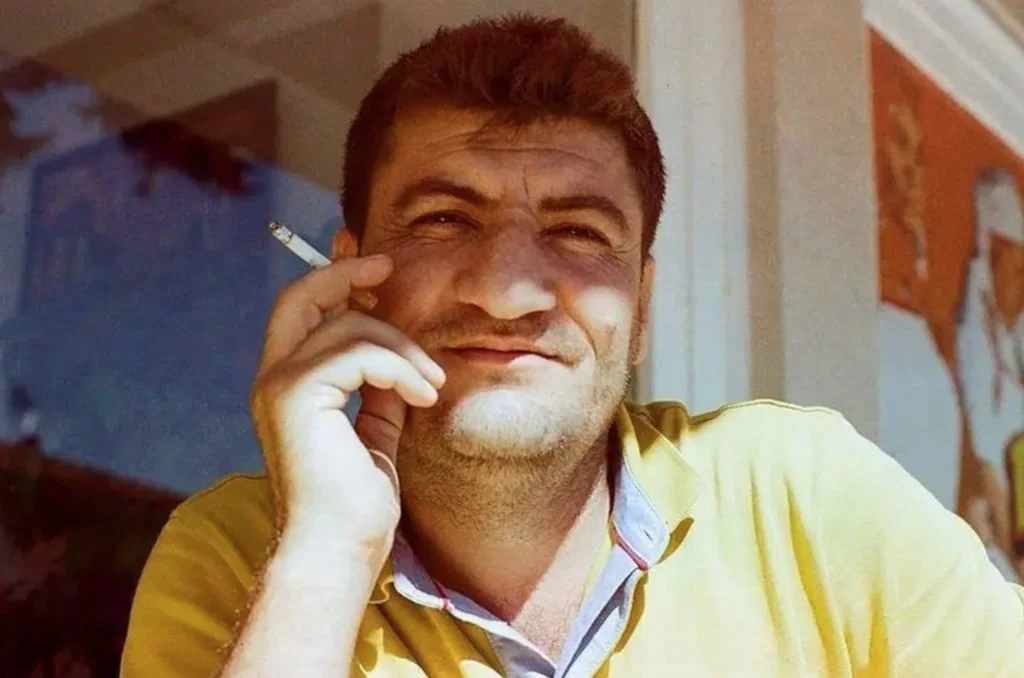

Raed Fares paints one of his protest banners.

By mid-2011, weekly protests swept Syria. Every Friday, Raed photographed them and posted to social media. What set Kafranbel apart was the creativity: banners written in English as well as Arabic, paired with some of the Middle East’s most iconic political artwork of this century, targeted to his fellow Syrians but also to the world that was watching events unfold. Raed became known as "The Banner Maker of Kafranbel." He crafted slogans and shared credit with the artist Ahmad Kalil al-Jalal and journalist Hammoud al-Juneid, spreading the protest messages far and wide. At first, protests were held despite the fact that the Syrian regime and its secret police were a constant threat. Every week, Raed and others risked their lives to let their voices be heard. By 2012, however, the pro-democracy forces of the Free Syrian Army had liberated Kafranbel, and the messages were aimed at freeing the rest of the country from the tyranny of the Assad regime.

Raed was smart, and my God, he was funny. His banners were as witty as South Park, often pulling from pop culture, sometimes from Western news cycles, but always mixing humor with biting critique. In one, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad is depicted as Gollum from The Lord of the Rings. Another banner read, "There is no egg in eggplant, no ham in hamburger. But let's face it, there is an Ass in Assad."

When the Boston Marathon bombing killed three people in 2013, Kafranbel sent its condolences to Boston, and soon afterward to the family of Martin Richard, an eight-year-old killed in the attack. "Martin Family! Syrians know what it’s like to lose loved ones by immune criminals." And when Robin Williams died in 2014, Kafranbel quoted his Aladdin character, the Genie: "To be free. Such a thing would be greater than all the magic and all the treasures in all the world." I cry as I write this because the people of Kafranbel, and Raed’s team, sacrificed everything—their possessions, homes, loved ones, and often their lives—for that freedom.

Raed was uncomfortable with the fame his banners brought but used it to spotlight Syria’s suffering. Raed's greatest legacy, however, was not his banners.

After the Free Syrian Army liberated Kafranbel during the summer of 2012, after more than a year of the regime's brutal crackdown, things should have gotten better for everyone. Instead, they got far worse. The Syrian regime and its allies relentlessly pounded the town with airstrikes deliberately designed to inflict maximum suffering. As airstrikes intensified, Raed took action. He organized spotters who tracked aircraft and broadcasted warnings over a radio station he helped develop, dramatically reducing casualties. He even made sure everyone in the town had access to working radios. Realizing he had built a fully-functional radio station that was mostly dead air, he used "Radio Fresh" to start a conversation about what the "liberated city of Kafranbel," and indeed what a free Syria, should look like. Radio Fresh aired political conversations, children’s programs, and discussions on secular democracy, women’s rights, and leadership—topics radical even among his allies. It was Syria's PBS, NPR, the National Weather Service, and a police scanner, all in one.

Raed wasn't just making a radio station, he was forging a new society in Syria from scratch. When the Syrian government fled Kafranbel, it left a vacuum. Local elders stepped in, and a makeshift militia kept the peace. But Raed and others knew that without real governance, chaos and fear could take over. The town needed schools, infrastructure, health care, policing. Raed played a key role in shaping discussions about a free Syria’s future. Kafranbel would be a beacon of democracy, and Radio Fresh’s reach was expanding. Raed wanted to have a serious conversation about what Syrian society should look like, and he was willing to discuss any and every idea, even if it angered hardline Islamist groups that had begun to take over as the conflict continued to become more desperate.

Raed was like a combination of Thomas Jefferson, Thomas Paine, Betsy Ross, and a dose of Matt Stone. Everyone knew he was behind the banners and Radio Fresh. And when hardline Islamist and jihadist groups like ISIS or later Hay'at Tahrir al-Sham took notice, they saw him as a threat. The Syrian regime had wanted Raed dead, but once the Free Syrian Army liberated Kafranbel, he faced new threats from extremists now living in the town. They harassed and bullied him—but Raed always confronted them head-on. When Al Qaeda elements kidnapped him, he told them bluntly that killing him would only bring them problems because he was so well-liked; he walked away alive.

Eventually, a jihadist group put a hit on him. Raed faced them again, politely refusing their ultimatum to stop his work. Raed was always polite.

Not long after, Raed came to America to share his story, hoping that U.S. leaders would take action against Assad before jihadist groups took hold. He visited Boston, where we finally met.

A Giant Among Us

Raed was the first person I saw when I entered the room because he was a giant—tall, built like a brick wall, but kind. Though he could have easily overpowered these jihadists with his bare hands, violence was not his way. Raed survived not through brute strength but because even his enemies liked him too much to kill him—at least, at first. He spotted me at the same time I spotted him and interrupted his conversation to come over and give me an embrace. "It is good to finally see you, my friend."

After he spoke to the crowd, the two of us talked for hours. In broken English -- one of the hallmarks that gave his banners character -- and with the help of an interpreter, he told me all the things Radio Fresh was trying to accomplish and explained how he brought together all these different sides, all the points of view that were competing to decide what was next for Syria. Raed knew that his vision of democracy was under threat from all sides, but he embraced it, willing to engage with everyone. He knew that he could not force his beliefs on people who would not accept them. He also knew he could never stop advocating for what he thought was right. Dialogue and compromise were the only paths forward.

But not everyone was willing to participate in a conversation. Powerful forces sought to accumulate more power and use that power to shut down all other debate. This meant they wanted to shut down Raed, and since he was not willing to shut his mouth, they were ready to kill him.

Why would you go back to that, I asked. He shrugged off assassination threats, saying, "Many want me dead, but more like me alive. For some reason, people like me. Or maybe they’re just afraid because I’m tall." He joked a lot but never cracked more than a wry smile.

PROJECT OF GENERATIONS

If you’re wondering what any of this has to do with Trump, it’s because of what Raed told me next—a message that right now I can't stop thinking about.

We’d discussed my going to Kafranbel to write about the movement. I was hesitant, but Raed’s passion was infectious. "Stay with me, in my home. You just have to come to Syria." I said yes.

But before I went, I needed to know how he stayed so brave, because I did not feel brave at all. Dozens of people, often people we knew, were dying every day. The threats from the regime were only eclipsed by the looming presence of the Jihadists. I asked him how he stayed positive surrounded by so much death. He smiled, gently, knowingly, and these are the words that echo in my head today:

"Oh, I will die before Syria is fixed, even if they don’t kill me. Syria took many years and years to get this bad. So it will take many, many years," he said, before his interpreter added, “generations.” Raed nodded. "Yes, generations. Sorry for my poor English."

“I won’t see the end, but I’ve seen the beginning. There will be many problems, but Syria will be free! It’s started! You have to come and see it yourself!”

This is where we find ourselves today. If Trump’s win has us in a crisis, we have to remember: our problems did not begin with him. A Harris win wouldn’t have erased the apathy, cynicism, racism, nativism, or division. Four years of Biden didn’t change it; four or eight years of Harris would not either. This isn’t about policy or turnout or messaging. There are fundamental issues deeply broken in our politics and society, issues that took generations to develop, issues that we have never agreed upon or resolved, even if laws from time to time have codified temporary answers.

Things feel like they’re falling apart because they are. But society has changed at a lightning pace. My grandmother, 98 years old and still alive today, lived through World War II, the birth of NATO, legalized abortion, the first time women were allowed to open bank accounts, and gay marriage, just to name a few things. Almost everything we know about our world is less than one hundred years old, from our political beliefs to our institutions to our technology. Our frustrations with progress or pushback come from this speed of change. But changes are always met with equal resistance. This is a basic law of physics and politics. Some take decades or even centuries to realize.

Raed’s legacy reminds us that meaningful change takes time. We can’t expect one election, one policy, or one leader to mend a society’s deeply entrenched issues. Raed, or the Free Syrian Army, could not eliminate Jihadism or sectarianism by cutting them out of the conversation, nor by violence or force. Raed knew that the only way to change things, to permanently change things, was to change hearts and minds. When Syrians accepted democracy in their hearts they would be free, and in order to do that he was willing to talk with the Jihadists and the sectarians, even if they would rather kill him than engage. Here in America, too, we must find ways to talk across our divides, to seek understanding where agreement feels impossible. We cannot force others to change, we must convince them. There simply is no other way.

Take Roe v. Wade as an example. Today, many fear that Christian nationalists will set back abortion and reproductive rights, but Roe was never a popularly mandated law. It was a ruling by seven Supreme Court justices, rather than a consensus across our society. The recent reversal reminds us that unresolved issues can’t be settled in the courts alone; they need dialogue and a shared commitment to lasting solutions. For 50 years many of us have deluded ourselves into thinking Roe was settled law, but in reality it was a repressed issue, artificially and temporarily capped by the Supreme Court, artificially and temporarily uncapped by a different Supreme Court. Like so many issues of our day, we can't move forward because we are still fighting about this issue, decided decades ago,

What Do We Do Next?

A man whom I respect greatly, John Berry, recently introduced me to a quote from the late American community activist and thinker Saul Alinsky: "People cannot be free unless they are willing to sacrifice some of their interests to guarantee the freedom of others. The price of democracy is the ongoing pursuit of the common good by all of the people."

This is what Raed was willing to do. We begin the long project of finding a way to coexist in a democracy where no one’s rights hinge on the vote of a small group of people in a swing state in a single election cycle. And we’ll have to swallow bitter compromises.

We have to ensure that someone's marriage will not be dissolved depending on the will of ten thousand voters in Wisconsin. In order to do this we may have to accept that it's ok if some people don't want to bake our wedding cakes. We're going to have to codify that a woman's personal decisions about her body should be between her and her doctor, but in order to do this we may have to agree that no federal money will ever go to abortion and no abortions will be held for non-medical reasons after a certain gestational time. Yes, global climate change is real and a deadly threat, but we're almost certainly going to be forced to agree that people can drive whatever vehicles they want even if they're heavy polluters, though we can hopefully find a compromise between gas mileage and freedom of choice. We're going to have to work together to find some sort of compromise on voter ID laws and gun rights and every other major wedge issue, and we are probably going to have to get to the point where no one, no one at all, is happy with the results.

To live in a democracy is to accept that we’ll disagree—and that real progress is achieved not through winning votes but through thoughtful arguments and engagement. We can dismiss Trump supporters as women haters and racists. They can dismiss us as Godless anti-men communists. Raed could have dismissed hardline Islamists as radical extremists (which is what he believed) and they dismissed him as an anti-religious infidel. Raed was killed for his desire for dialogue, but Raed’s words taught me that to sacrifice is to build something bigger than ourselves. Democracy demands we work toward a common good that respects all people. Raed’s vision was simple: allow everyone to have a place, and let ideas compete, not by force but by merit. We have to build a society where no one feels they must control another to protect themselves. We can't pass a law to destroy misogyny or racism, we have to teach something better. We have to build on dialogue, even if the conversations take longer than we've got.

That's not easy to accept. It's just not. And we can mourn this reality, but we cannot be blind to it.

Raed’s dream was one of radical inclusivity. His model is one we must embrace: broad coalitions, principled compromise, and the patience to build something sustainable. He stood for change he might never see, knowing it takes generations to heal and rebuild a society torn by violence and hatred.

The day after I met Raed, he flew back to Syria. When he reached his doorstep, gunmen shot him three times in the chest. Miraculously, he survived -- Raed was tough. Four years later, men in an unmarked van hunted him down and killed him. He died knowing that Syria was a horror show, but he did not lose hope because what he stood for—the idea that democracy takes time, sacrifice, and open minds—lives on. Raed knew he might never see Syria free, yet he believed every step counted. Like him, we may not see the end, but we can push forward. There will be setbacks, but if we hold to Raed’s hope and resilience, we will one day see a society that truly embraces freedom and dignity for all.

Freedom for all.

"It's started! You have to come and see it yourself!”